This is a daily figure exercise from a few months ago and I'm posting it here as a means to explore something I've found to be a bit puzzling about our time.

Although it's difficult to tease out what is genuinely authentic on social media sometimes—I've noticed a common trend or theme among much of the modern figure work I've encountered; the public doesn't really care to see the faces of people they don't know. At all. Especially if they are attached to a figure. And this is something I've increasingly become aware of when posting drawings or paintings of my own work to social media.

Maybe it's always been this way to some extent or another and I've just never noticed it. But, I look at the work of accomplished contemporary American artists like Zhaoming Wu or Steve Huston, and nearly all of their work that includes a figure or body discludes the face of the subject. Or in the least, their identity as a person is mostly obscured. And this trend goes beyond just the work of contemporary American artists. It extends to mannequins as well and to items as obscure as faceless angel figurines on Amazon.

Artist: Zhaoming Wu

Artist: Steve Houston

Faceless Mannequins

A Faceless Angel Figurine

In all the history of art and western culture I don't think there is a period prior to the last 30 or so years where this was a cultural trend in design and art. And I have yet to encounter any kind of cultural historian who has articulated this—or confronted as to why this has happened.

As an artist, who has spent a lifetime working to understand and communicate the intricacies and nuances of expression transmitted by the human face—I've found this to be incredibly strange. Christ, there is an entire area in the brain purely dedicated to perceiving faces; the fusiform gyrus. And there's really not that many famous or beloved figurative works prior to the late 20th century where the figure's identity is unimportant or deliberately obscured.

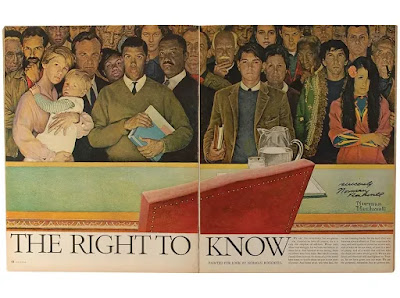

How is it now that we don't want to look at the face of humanity? Especially when it comes to strangers or unfamiliar faces. If one looks at art work in popular culture prior to the 80s, especially in commercial illustration, it is filled to the brim with human faces of all types. And Norman Rockwell is a perfect example of this. It's nearly all quirky, idiosyncratic, everyday strangers—the common man/woman.

Although I can't claim to wield the intellectual tool set or resources to confront this question in depth; I most definitely think something has happened on a deep cultural level in the last 30-40 years that has been traumatic in ways we see one another (strangers in particular) and it's gone on mostly unrecognized by the wider culture. Especially in America.